Listed among the four castles defending the village of Avigliano Umbro and the Byzantine Corridor, Santa Restituta has long intertwined its history with a very particular tree: the chestnut tree.

If the defensive function of Santa Restituta is still visible today from the houses that, leaning against each other and interspersed with imposing towers, act as a city wall, to understand the economic importance that the chestnut tree had in all its parts we must go back to the Middle Ages.

In fact, it was the Benedictines who took care of the trees: with pruning and grafting, they managed to optimize not only the production of “strong construction wood”, but also of chestnuts, essential for the survival of the less well-off people. The communantia (land for civic use) of Santa Restituta gravitated first in the orbit of Baschi, then of Todi which, even in the face of the demands of the Apostolic Chamber, always considered it direct municipal property, as attested by the “recognition and termination” of 1294 that delimited its borders.

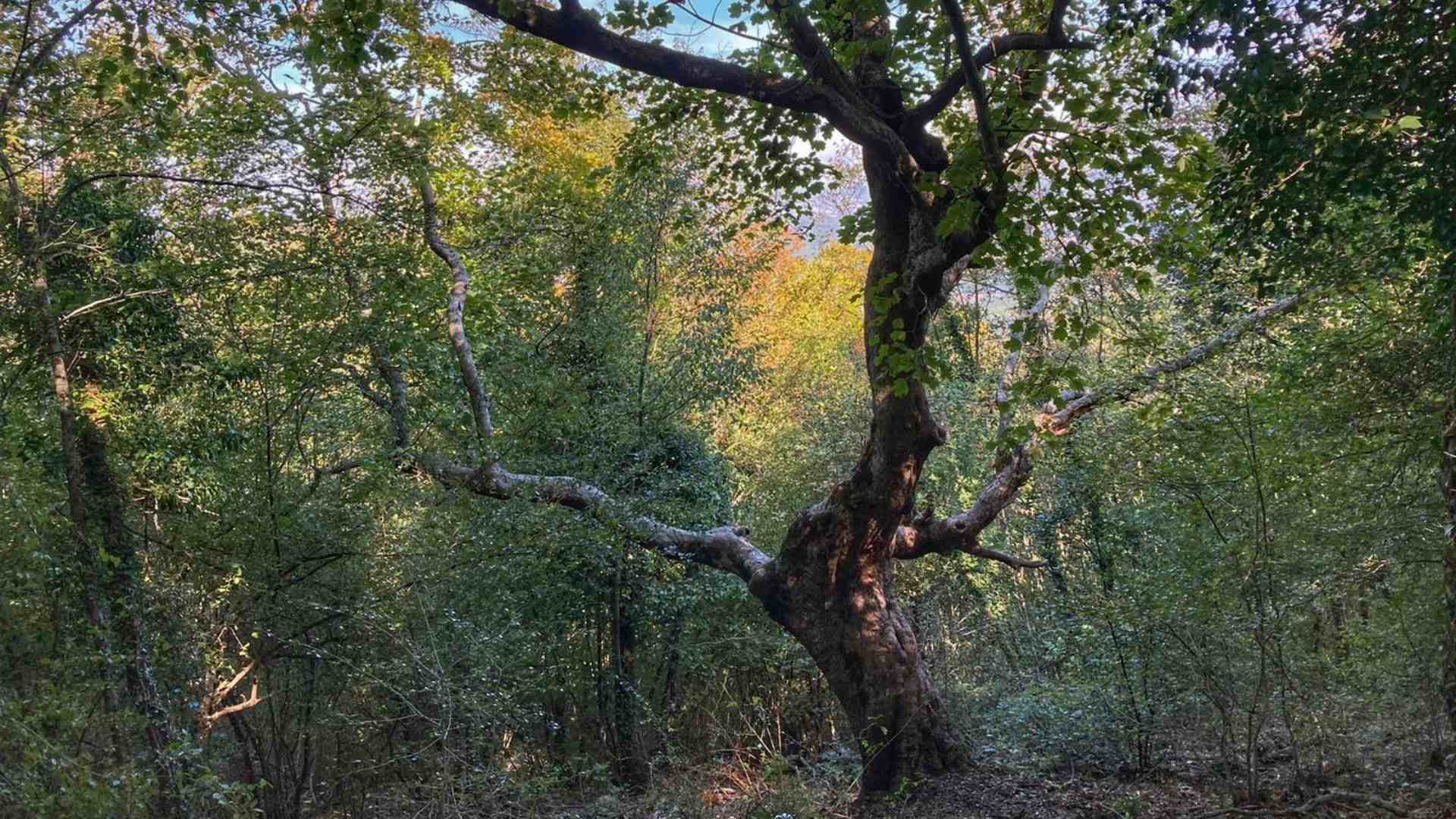

Of the dense woods that were so coveted by the neighboring powers, there still remain centuries-old chestnut groves interspersed with areas covered with flowering ash and maples, including the so-called acerone, a monumental tree considered one of the oldest specimens in Europe.

Not only that: hidden by the mountains surrounding Santa Restituta there are some curious emergencies, not only historical, but also naturalistic.

In fact, if on Mount Pianello it is possible to see the remains of the primitive settlement – dating back to before 1220 and known as Castello di Restituto – on the side of Mount Aiola there is a karst cavity called Grotta Bella, discovered in 1902 but explored only between 1971 and 1973. From the entrance there is a series of rooms full of stalactites, stalagmites, columns and angel hairs which, in addition to creating an evocative stone labyrinth, have returned evidence of different eras that attest to human presence from the Neolithic to the Roman Imperial Age.

These findings have allowed us to understand how the cave, over the centuries, has changed its intended use several times. In fact, if for the Umbrian people it served as a meeting place, with the Bronze Age it took on sepulchral purposes, documented by ceramic materials with symbolic designs and by human remains. From the 6th to the 1st century BC it took on a religious purpose, as evidenced by votive offerings dedicated to Mars and other deities who protected livestock farming, agriculture and also people at war or who were sick. After the frequentation in the Republican Age characterized by black-glazed ceramics and coins, in the Imperial Age the aggregation methods of the area changed again, testifying that the site was occupied in an increasingly sporadically. Today some of the findings are preserved at the Plant Paleontology Center of the Dunarobba Fossil Forest.

Returning to Santa Restituta, it is worth climbing the steps around which the entire village develops. In this way you will arrive directly at the Church of Santa Maria Novella, which has housed, since the 17th century, the relics of the saint martyred in Sora by the Emperor Aurelian that the devotees, in 1551, moved from the town in the province of Frosinone to the small cemetery church that bears her name. Today in the small parish church of Santa Restituta it is possible to admire a cycle of frescoes and a wooden statue of the Madonna del Pero from the 15th century.

Eleonora Cesaretti

Latest posts by Eleonora Cesaretti (see all)

- The Deposition of Cannara, a work that ended up in oblivion - April 8, 2025

- Of devotion and chestnut woods: the village of Santa Restituta, a jewel to be discovered - February 11, 2025

- The secret rooms of the small Della Corgna palace - January 9, 2025