Widespread since Roman times and created to bring together anyone who practiced the same profession, corporations (or collegia) were soon used as an instrument of local control by the imperial power. In the Middle Ages they evolved and became associations of entrepreneurs whose main purpose was to defend their interests with the authorities: in Perugia the two most powerful were the Collegio della Marcanzia and that of Cambio. Traces of the intensity of their power remain in the two magnificent rooms where the two corporations met.

Although in the rest of Europe they took on peculiar traits and in Italy they had names that differed from territory to territory – arti in Tuscany, fraglie in the Veneto hinterland, scole in Venice, paratici in Lombardy, gremi in Sardinia and colleges in Perugia – among the guilds common traits can be identified, relating to the primary purpose of each corporation to defend the exercise of its trade, its product and those who created it. For example, the quality of manufactured goods was protected by controlling raw materials, work tools and manufacturing processes, as well as combating what we would today call fakes; at the same time the principle of non-competition was promulgated, although a hierarchical order existed among the members which influenced not only the carrying out of the activities, but also the earnings. Finally, the new generations were trained: the children entered the workshop at an early age to learn all the tricks of the trade.

Even among the different arts there were hierarchies, so much so that Major, Median and Minor Arts were distinguished, different from city to city: the economic power, the number of members, the preponderance of each profession within the urban economy and the participation of its adherents in political life caused visible divisions in major public events, such as the processions for the festivals dedicated to the patron saint or the Virgin. In Perugia, in 1342, the first to parade during the procession for the patron saint San Costanzo were those enrolled in the Collegio della Mercanzia, followed by those of the Cambio, the Calzolari and so on.

A little curiosity: the saying “going for the major” derives precisely from the guild system: belonging to the major arts ensured respect and trust.

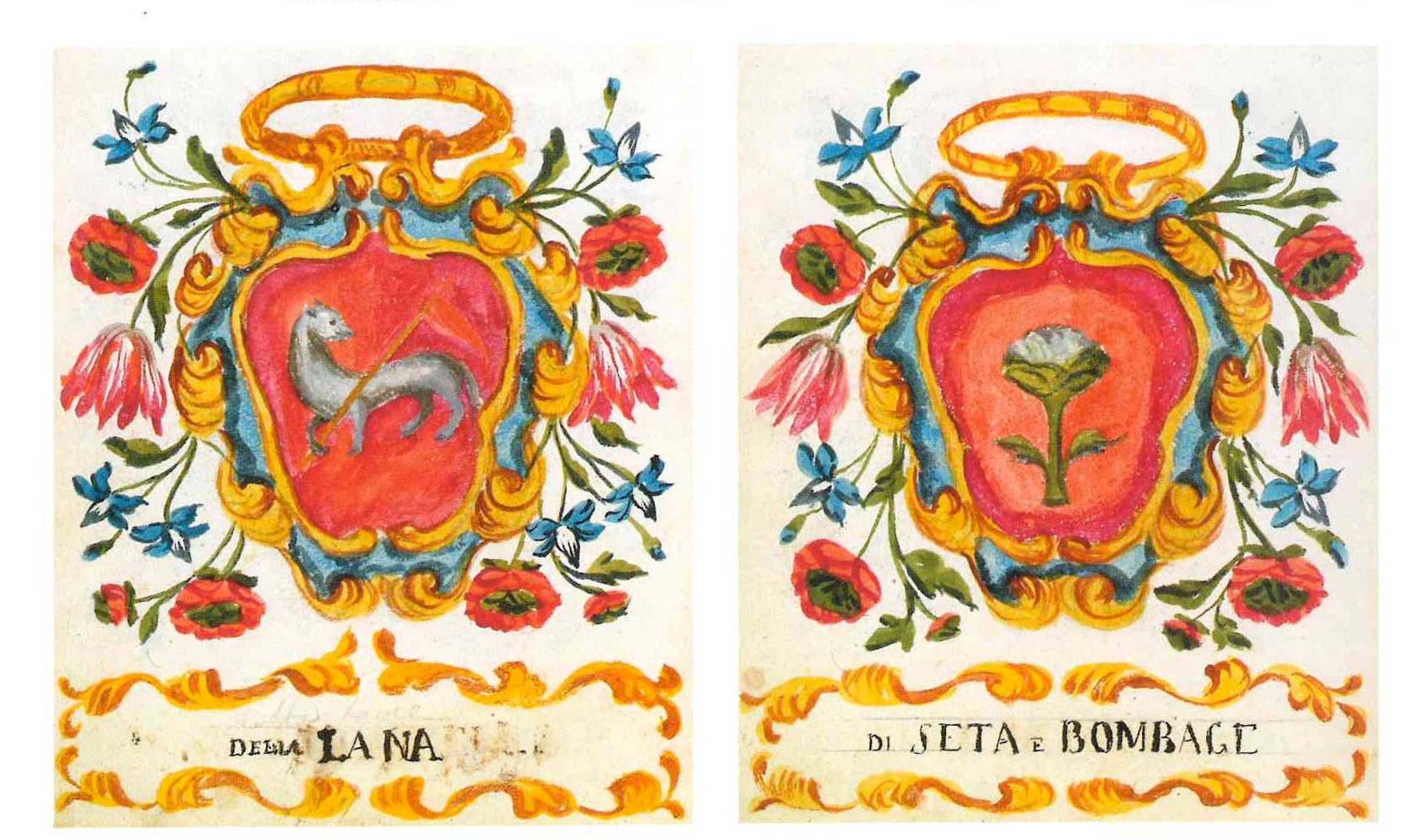

The Mercatores Corporation

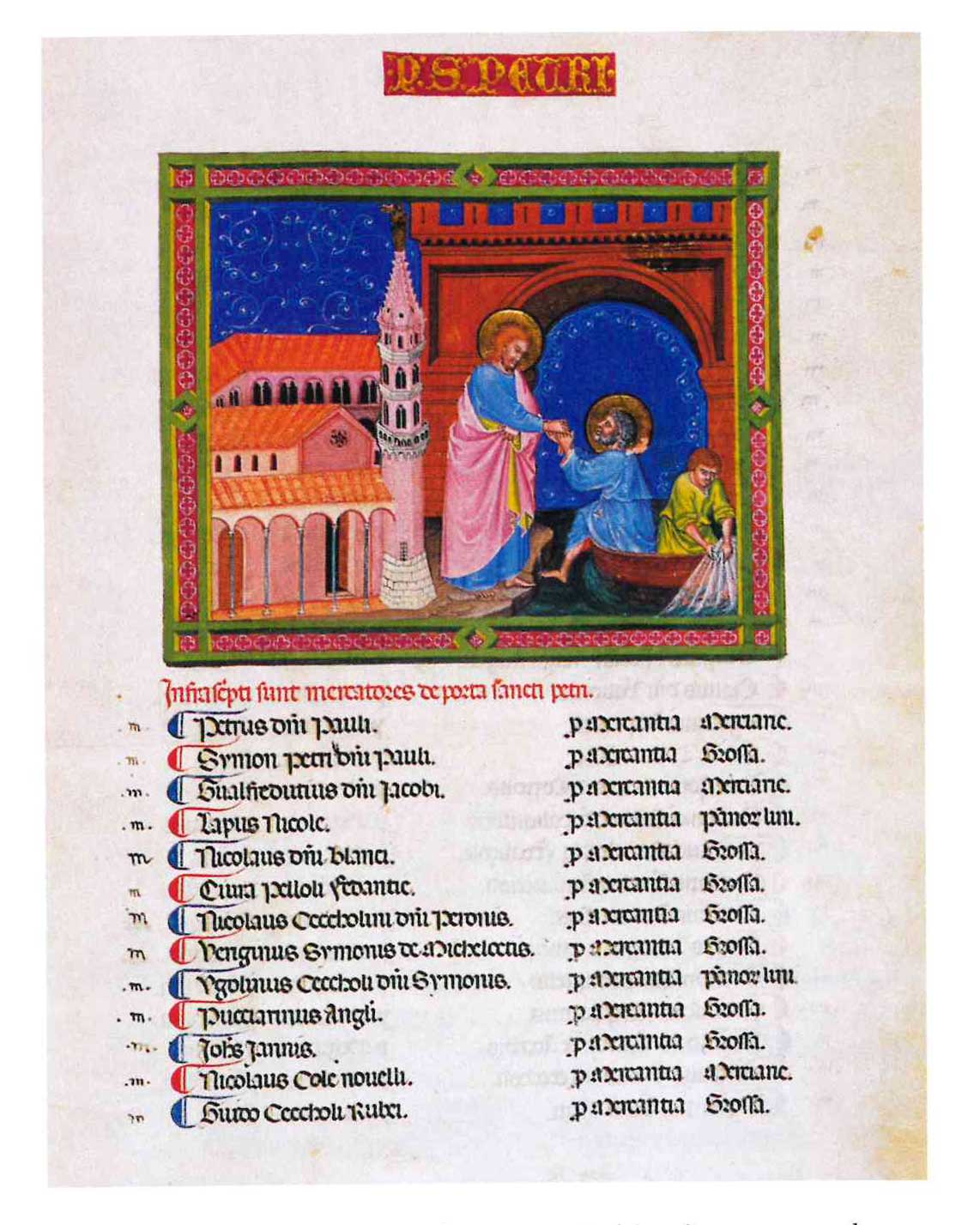

​The existence of the institution was documented as early as 1218 and the strong political influence it exercised was evident from the fact that it was responsible for appointing the first two of the ten Priors who governed the Municipality. He also collected the oath of the highest officials, provided the magistrate with prey in reprisals, moderated the collection of taxes, guaranteed the captain and other foreign officials, and established the official rate of currency.

Of the Collegio della Mercanzia we still have the statutes and the registers of 1323, 1356 and 1599. If the registers contained the names of the members, the statutes regulated the admission requirements and the exercise of trading, individual or corporate, unfair competition , mediation, weights and measures, the methods of display and sale of goods, the consequences of bankruptcy, the certification of writings, the work of journeymen, commercial jurisdiction.

​

The face of power: the Audience Hall

​In 1390 the Municipality of Perugia, to compensate for a loan received for wars and famines, gave the College some rooms on the ground floor of the Palazzo dei Priori, which the Guild had covered with precious boiserie in walnut, fir and poplar wood . The Nordic inspiration of this decoration is counterbalanced by the glyph that embellishes it, a clear reference to oriental art, a representation of the two geographical extremes touched by the merchants in their frequent travels. Outlining the perimeter of the Hall is the seat for the merchants who took part in the meetings, while the seat with Gothic style carvings was reserved for the officials. The pulpit, decorated with the four cardinal Virtues and griffins, was instead intended for the merchant judge and is also a rather rare testimony.

The Noble College of Change and the Divine Painter

The main objectives of the art were to supervise the legitimate exchange of money and to pronounce sentences on civil cases within the scope of its competences, for which it assumed the functions of a court. Of great impact is the collection of monetary weights (550) for coins circulating in Perugia and in the Papal States between the 15th and the second half of the 19th century. Coin weights were fundamental for controlling the actual value of gold and silver coins, established based on their weight and the percentage of precious metal in the alloy.

The headquarters is also precious, completed in 1457 after five years of work and included in the Palazzo Pubblico, in whose decoration (begun in 1490) some of the most esteemed artists of the time took part. Domenico del Tasso created the counter and the rear panels, while the golden terracotta statue of Justice was created by the hand of Benedetto da Maiano. But it is the Divine Painter Piero Vannucci who is responsible for the pictorial decorations perfectly fused with the wooden inlays that give the Audience Hall the timeless appearance that characterizes it. The work almost certainly began with the seven vaulted ceilings with the personifications of the zodiac signs in the planets, connected to each other through those fantastic representations – cherubs riding goats and panthers, satyrs, harpies and so on – which will later be identified as grotesque . It was precisely in those years, in fact, that Nero’s Domus Aurea was rediscovered and, precisely in those half-buried caves, a series of frescoes had been found which had first stirred the soul of the artists and then ended up becoming the progenitor of a renewed attention to the ancient world that will characterize the entire 15th century.

In the grotesques of the Audience Hall of the Collegio del Cambio – in all likelihood entrusted to at least two of Perugino’s collaborators – there are also references to local heraldry and typical ceramic decorations; yet, there is no qualitative difference compared to the Master’s frescoes, placed in the upper part of the walls and above the posters arranged along the perimeter of the room. The frescoes, divided into five paintings, represent the triumph of the Virtues: the four cardinal Virtues are embodied in exemplary figures from Greek and Roman history, while the three theological Virtues are allegorically represented by the lunettes with the Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor, the Nativity and the Eternal Father with Prophets and Sibyls. The theme of the concordance between pagan wisdom and Christian wisdom was developed by the humanist Francesco Maturanzio, inspired by the Factotum et dictorum memorabilium libri by Valerio Massimo. Maturantius also dealt with the Latin verses that appear in the explanatory tables.

It is precisely on the left wall of this room that Perugino’s self-portrait stands out, with a trompe-l’oeil effect, above words that express all his satisfaction at the fame he has achieved: «Pietro Perugino, illustrious painter. If the art of painting had been lost, he found it again. If it had not yet been invented, he brought it to this point.”

Colleges over time

As the years passed, the characteristics of the Colleges changed: the decline of trade, the emergence of the noble class, marital intermingling, the victory of the noble party of Braccio Fortebracci and some statutory changes meant that the corporations were transformed into bodies of the Perugian patriciate and, to be admitted, one had to provide irrefutable proof of one’s nobility. With the Napoleonic era, the institutional functions also ceased, but the two Colleges continued to maintain their aristocratic character unchanged until the Statute of 1983. Today it is possible to visit the magnificent headquarters of these two ancient institutions, enclosed in the historic center of Perugia, or participate in initiatives that are periodically organised. For more information see:

Eleonora Cesaretti

Latest posts by Eleonora Cesaretti (see all)

- The Deposition of Cannara, a work that ended up in oblivion - April 8, 2025

- Of devotion and chestnut woods: the village of Santa Restituta, a jewel to be discovered - February 11, 2025

- The secret rooms of the small Della Corgna palace - January 9, 2025