Città della Pieve

PROVINCE:

Perugia

WEB:

For tourist information:

Centro Servizi Turistici

Piazza Matteotti

Tel: +39 0578 298520

Città della Pieve

Città della Pieve is REGISTERED TO:

discovering the village

“How beautiful it seems to us as it develops on top of a hill with the tranquil line of its houses. Nothing excessive or contrasting. The slopes are left to joyful greenery, to crops and olive trees. A few bell towers dominate alone towards the middle of the line. What a strange city! Is this how picturesque beauty is understood in the homeland of Perugino? I am eager to know.”

Thus wrote the French art historian Jacques-Camille Broussolle in front of the spectacle of Città della Pieve which, located on the hill that the Romans called Monte di Apollo, is the last Umbrian bastion before reaching Tuscan land.

Not much has changed since Broussolle’s late 19th-century Umbrian pilgrimages, since one of the peculiarities of this settlement, subjected first to the Etruscan locumonia of Chiusi and then to the Roman municipium, is that it has maintained an almost unchanged appearance from 1250 onwards. Until that annus horribilis in which Perugia, taking it back after yet another rebellion, forbade it from expanding, Castrum Plebis Sancti Gervasi, a fortified Lombard parish, had experienced an intense demographic increase thanks to the marshy Valdichiana and the proximity of the Via Romea Germanica and the Via Francigena, which had fueled a flourishing trade in bricks, wrought iron and crimson cloth.

At least until 1188, when it fell under the dominion of Perugia: the conflicts with the new governors were not long in coming, given the pro-Ghibelline orientation of the nobles of Pieve; nevertheless, the perfect opportunity to free itself from this yoke presented itself only in 1228, during the conflict between the imperial and Sienese troops against the Umbrian cities. What had by then become Castel della Pieve took advantage of this to rebel against Perugia and place itself under the protection of Frederick II of Swabia, a situation that lasted until the fateful 1250, when the Augusta took it back and punished it by forcing it to provide as many bricks as were needed to pave the Piazza del Sopramuro, in the historic center of the Umbrian capital.

That that first sedition was violently suppressed is demonstrated by a curious find. Under the apse of what is today the cathedral dedicated to Saints Gervasio and Protasio, there is a polygonal building supported by arches and massive sandstone columns. Long thought to be a crypt, it is probably nothing other than the loggia of the Palazzo dei Consoli, destroyed in 1250, following the reconquest of Perugia.

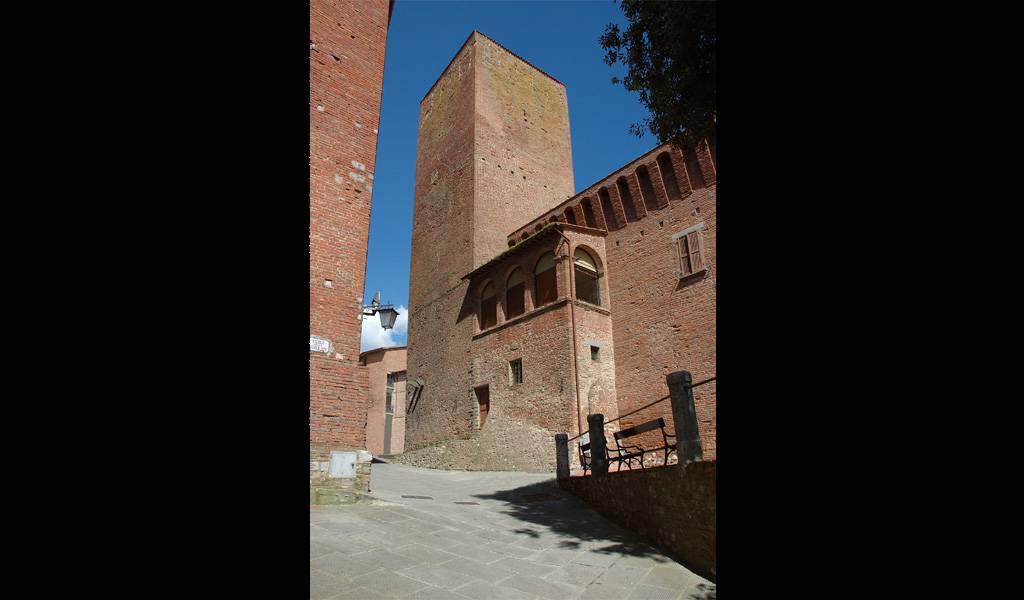

Some of the most characteristic civil and religious buildings of the village also date back to this period, such as the new parish church, the Palazzo dei Priori, the Civic Tower (or del Pubblico) and the Bishop’s Tower. The latter, located at Porta Fiorentina, still allows you to follow the route of the medieval walls up to Porta Romana, also known as Porta Santa Maria or del Vecciano: according to the nineteenth-century historian Antonio Baglioni, they also included a cliff known as Sansalvatico, where there were cultivated plots that provided a great advantage during sieges, as well as quarries for the extraction of clay and sand that were used for the production of the famous Pieve brick.

Along the route of the walls in 1326, the Rocca Perugina was also built, wanted to control the unruly population of the place. The works were entrusted to the Sienese architects Lorenzo and Ambrogio Maitani, who equipped it with a moat, a drawbridge and five towers (Maestra, del Castellano, del Prato, del Frontone, dei Maitani) that could send fire signals.

The construction of this imposing fortress should not cause any perplexity, as the spirit of rebellion of the Pievesi was hard to die, and the Perugians had also understood this: proof of this are the uprisings of 1375 – when Castel della Pieve allied itself with Milan and Florence and joined the League of Liberty, attracting the interdiction of Boniface IX to celebrate religious functions together with the intervention of leaders in the pay of Perugia such as Biordo Michelotti and Braccio da Montone – and of 1526.

This situation of political instability reached its peak in 1528, when the French troops of Francis I, who arrived to help Clement VII during the Sack of Rome, devastated the village. The following year the Pope placed it under the direct control of the Papal State, installing governors of his own appointment in the Rocca of Perugia. With this change of function, the towers of the fortress were also reconverted: they were lowered and used as a prison. A little later, the Pieve dei Santi Gervasio e Protasio was also expanded, so much so that it was built against the Torre del Pubblico (or Civica), a structure that had sighting purposes and which, in the same period, was raised by a good 7 metres, reaching 39. Both in the pieve and in the Torre del Pubblico one can recognise an older part – made of backfill material, mostly travertine – and one which is the result of the sixteenth-century expansions, in brick.

In 1550, Pope Julius III, to repay his sister Giacoma for a large loan, decided to donate the territory of Castiglion del Lago and Chiugi to her. On the edge of these lands, Castel della Pieve was donated to Giacoma’s son, Ascanio della Corgna, who became its perpetual governor: one of his first interventions was the construction of a sumptuous palace, which he entrusted to his friend the architect Galeazzo Alessi. Ascanio would only see the beginning of the construction of the splendid u-shaped residence, with three floors and a cloister with a cistern: a series of rebellions, more or less legitimate incarcerations and battles would keep him away from Castel della Pieve for a long time, of which he was subsequently forced to share the marquisate with his brother Fulvio. It was the latter who commissioned the splendid interiors of the family palace: the Muses in concert by Niccolò Circignani, known as Pomarancio, glorify the della Corgna family in the Sala del Governo, while the gods in banquet with their loves, inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses and skillfully painted by Salvio Salvini, decorate the Sala Grande. Today Palazzo della Corgna houses the library and some public offices, as well as the Museum of Natural History and the Territory dedicated to the geologist and paleontologist from Pieve Antonio Verri; among fossils, minerals and stuffed animals it is even possible to come across a curious artefact, the true nature of which was discovered only at the end of the last century. Left for a long time in the nearby cloister of San Francesco, this block of sandstone with a young man adoring the sun is none other than an Etruscan obelisk dating back to the 5th century, and is considered the oldest find in the entire district of Città della Pieve.

From the death of Ascanio onwards, Castel della Pieve was assigned to a series of governors, until, in 1600, Pope Clement VIII elevated it to a City, establishing the diocesan seat there and thus freeing it from Chiusi. The Bishop’s Palace, which was built under the direction of the architect Andrea Vici, today houses the Spazio Kossuth, a permanent exhibition of the Pieve Cavalli Cultural Association, with books by the equestrian journalist Giorgio Martinelli.

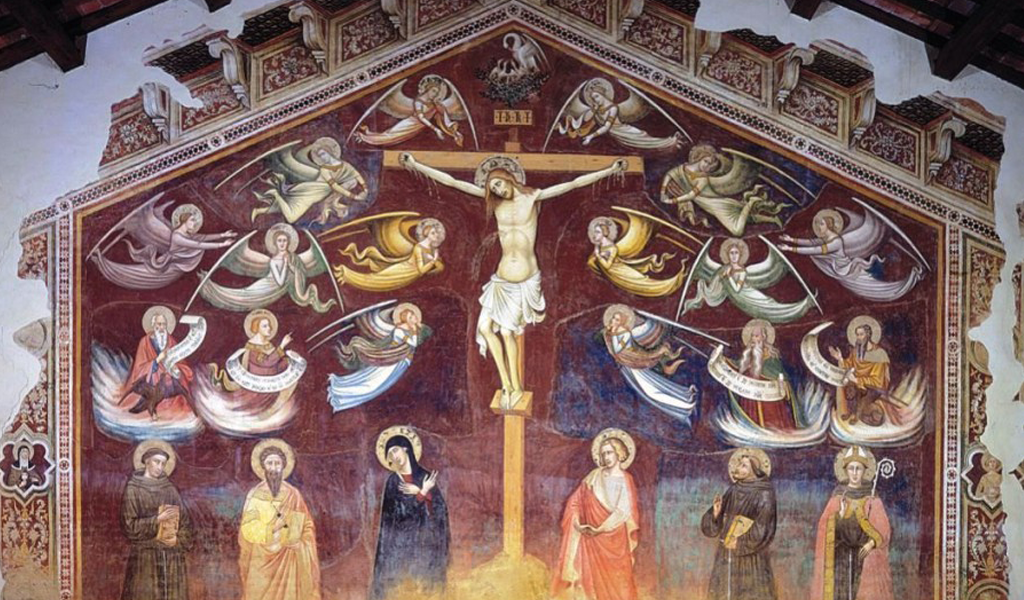

In the same 1600, the Pieve first became a Collegiate Church and then a Cathedral. The interior, while retaining a Latin cross plan with the nave flanked by three chapels on each side, takes on the baroque appearance that still characterizes it and which frames the works of the masters who were born or worked in Città della Pieve: the Baptism of Christ (1510) and Madonna Enthroned between Saints Gervasio and Protasio (1504) by Perugino – whose birthplace is also visible in Piazza del Plebiscito – as well as the Marriage of the Virgin (1606) and the Heavenly Glory by Antonio Circignani, also known as Pomarancio, the only surviving part of a pictorial cycle destroyed during a fire in 1783.

Other works by the two masters are visible inside the Museo Civico Diocesano – which also houses two sarcophagi and the rich funerary objects of the Etruscan Pulfna family, discovered in 2015 – in the Oratory of Santa Maria dei Bianchi – to complete the Adoration of the Magi took Perugino just 29 days to complete, settling for a paltry fee – and in the Church of the Santissimo Nome di Gesù, where the Beheading of the Baptist commissioned by Antonio Circignani remains as a reminder of the annexation of the Confraternity of the Mercy of Jesus and of Saint John the Beheaded to the Archconfraternity of Rome.

Also worth a visit is the Church of San Pietro, which houses – despite a series of moves to save it from the earthquake that hit the city in 1861 – Sant’Antonio Abate tra i Santi Marcello e Paolo eremita, also by Perugino.

The deconsecrated church of Santa Maria dei Servi, on the other hand, offers us the last, fascinating mystery of the “most wonderful city in Umbria, the perfect city”, to quote Broussolle: in the Chapel of the Madonna della Stella there was a splendid painting by Perugino, the Deposition from the Cross (1517). In 1700, during the construction of the organ, it was seriously damaged and therefore hidden in a cavity. There it remained, forgotten, until 1834, when the German painter and art historian Johann Anton Ramboux discovered it, determining its unique and inestimable value.

In Città della Pieve there is also one of the narrowest streets in the world: the Vicolo Baciadonne, 50 to 70 centimeters wide, which apparently arose from a dispute between neighbors who, hating each other to death, decided to separate their homes. The name derives from the fact that two people who pass each other could not pass by without kissing.

Città della Pieve has a plan that resembles an eagle: needless to say, this has favored a system of symbols linked to the terzieri, or the three social classes of the village (bourgeoisie, pedestrians and knights). Mentioned for the first time in 1250 in the act with which Castel della Pieve submitted again to Perugia with the twentieth-century recovery, the terzieri ended up coinciding with three areas of the city, as well as three parts of the eagle’s body: the head, facing Rome, corresponds to the Terziere Castello, which represented the class of knights; the Terziere Borgo Dentro, symbol of the bourgeoisie, is located in the belly, while the Terziere Casalino, class of pedestrians and farmers, is located in the wing and tail.

Each of them, during the year, organizes an event. The Borgo Dentro district, with its yellow and black livery, sets up Quadri Viventi in the basement of Palazzo Orca, characterizing each edition with a different theme. The Casalino district – in red, white and blue – organizes the Infiorata di San Luigi Gonzaga, while the Castello district, in green and black, recreates a monumental living nativity scene in the basement of Palazzo della Corgna. In addition, the Palio is held every year which, in addition to the historical parade complete with allegorical floats, sees three archers from each district challenge each other in the Cacce ai tori, or in the arduous task of hitting the silhouettes of the Chianina bulls mounted on a carousel.

Another event not to be missed is undoubtedly Zafferiamo, a festival that celebrates one of the most prized products of Città della Pieve, whose production is already attested in the Statute of Perugia of 1279. Initially, saffron was used as a dye for fabrics, and the event – held every year in October – offers activities that illustrate its various uses, without obviously neglecting the gastronomic one.