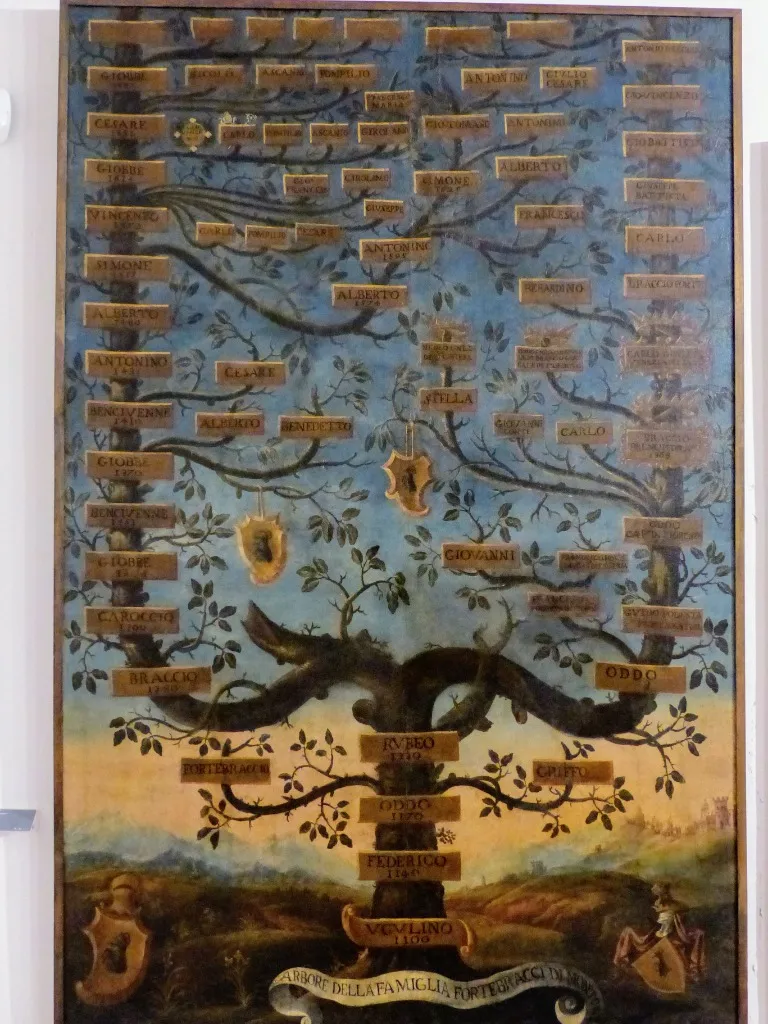

The history of Montone is closely linked to the Fortebracci family, of which the bloodthirsty leader Andrea, known as Braccio, is perhaps the most famous exponent. The traces of this noble lineage are witnessed by two interesting family trees, dating back to the beginning of the 18th century, kept in the Museum Complex of San Francesco di Montone.

The two representations, identical in content but not in form, were intended, one for the last residence of the Fortebracci and the other for the council chamber of the Town Hall of Montone. Thanks to these, we know that the lineage begins with the founder Ugolino, in the year 1100: two branches branch off from him, the main one of the Fortebracci – where the names of Andrea “Braccio” from Montone and that of his son Carlo are clearly highlighted, marked by a crown and sceptre – and the collateral one of the Giobbi. The lineage – which, until the late 16th century, was believed to derive from the Barcidi of Carthage, lineage of the famous leader Hannibal who had triumphed in the battle of Trasimeno in Umbria – reaches up to the generation of the last seventeenth century.

The two trees stand out in front of a hilly landscape in which it is possible to recognize Montone, nestled on a hill, with the Rocca and the Church of San Francesco. The coat of arms of the family is also present, a rampant ram which, according to the symbolism of heraldry, not only suggested the name and origin of the family, but also a tenacious and strong temperament that we know for sure can be attributed to its most famous exponent. To quote Enea Silvio Piccolomini (Pope Pius II, 1405-1464):

«Braccio was a handsome man, although handicapped on the left side; his speech was sweet and caressing; however, he had a cruel temperament to the point of laughing while ordering people to be tortured and torn to pieces with atrocious torments, and to delight in throwing poor people from high towers. In Spoleto he gave the order to throw a messenger who had brought him a hostile letter from a bridge. In Assisi he threw three men from a tower that rises in the main square. In the convent of the Friars Minor he gave the order to punish eighteen monks who had hostile feelings towards him, by crushing and crushing their testicles on an anvil. In Viterbo he had a prisoner immersed in a spring of boiling water called Pelacano […] Braccio believed neither in Heaven nor in Hell, was an enemy of the Church and of religion and absolutely unworthy of receiving religious obsequies.» (Enea Silvio Piccolomini, in Niccolò Ciminello, The War of the Eagle. Anonymous Singing of the 15th Century, edited by Carlo De Matteis, Edizioni Textus, anastatic reprint of 1996)

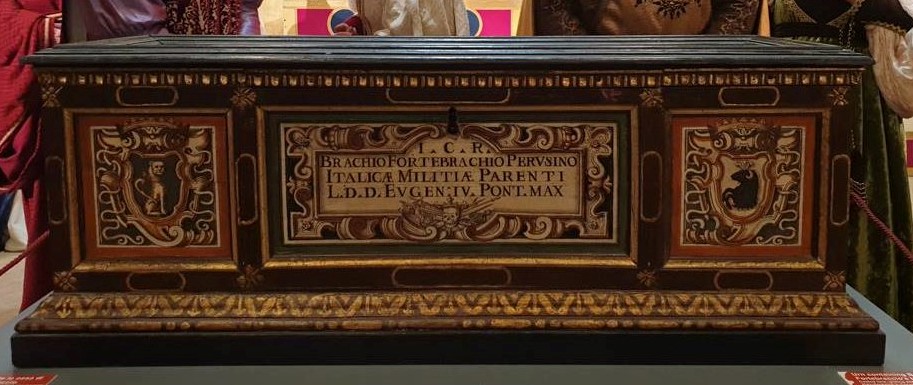

In the analysis of the two family trees, it must also be taken into account that, according to the inheritance law established by the Salic law – a code drawn up in 503 by the king of the Franks Clovis I to establish some legal norms that until then had only been passed down orally – “No (Salic) land can be inherited by a woman, but all the land belongs to the males, who are brothers of the woman.” The Fortebracci succession makes no difference and the only woman who appears in the line of descent is a certain Stella, mother of a Nicolò who brought back his uncle’s remains from L’Aquila. It was in fact under the walls of this city that Braccio met his death, whose remains now rest in San Francesco al Prato, the church of the Perugian nobility.

Leaving aside the countless political and war events that saw him as a protagonist for over forty years – including the two attempted sieges of the city of Perugia repelled by the population, the victory in the battle of Sant’Egidio against that Carlo Malatesta appointed by the Pope who earned him the Lordship of Perugia, the capitulation, in a chain, of Todi, Narni, Terni and Orvieto, the continuous clashes with Martin V and the two excommunications – it is interesting to take into consideration the numerous legends that circulated, for several centuries, around his death.

Like all stars (ante litteram) and the most controversial figures in history, there has been no shortage of conspiracy theories surrounding the figure of this leader who, indulging in his dream of naming Perugia as the capital of a regnum italicum freed from mercenaries and the power of Rome, had donated a new city wall, noble palaces, homes frescoed by artists of the caliber of Domenico Veneziano and Piero della Francesca, lodges for the protection of goods and merchants and bridles for the consolidation of the Sopramuro square to which he had given his name.

The various legends surrounding his last days of life agreed on the fact that he had been wounded under the walls of L’Aquila and then taken prisoner. For some, he was killed by the surgeon in charge of treating him who, intentionally bumped into by the winner Francesco Sforza, had stuck the scalpel in Braccio’s cerebellum; others maintained that he had been taken before Jacopo Caldora who, enraged by his silence, had killed him; a third theory claimed that, closed in on himself and refusing food and medicine, he had died in his cell a few days after his capture.

Only in 2013, 589 years after his death, the truth came to light: Braccio’s remains were exhumed for restoration. The reconnaissance revealed the presence of a hole in his skull, which confirmed that he died during the siege of the city of L’Aquila, probably on the spot.

Eleonora Cesaretti

Latest posts by Eleonora Cesaretti (see all)

- The Deposition of Cannara, a work that ended up in oblivion - April 8, 2025

- Of devotion and chestnut woods: the village of Santa Restituta, a jewel to be discovered - February 11, 2025

- The secret rooms of the small Della Corgna palace - January 9, 2025

«Braccio was a handsome man, although handicapped on the left side; his speech was sweet and caressing; however, he had a cruel temperament to the point of laughing while ordering people to be tortured and torn to pieces with atrocious torments, and to delight in throwing poor people from high towers. In Spoleto he gave the order to throw a messenger who had brought him a hostile letter from a bridge. In Assisi he threw three men from a tower that rises in the main square. In the convent of the Friars Minor he gave the order to punish eighteen monks who had hostile feelings towards him, by crushing and crushing their testicles on an anvil. In Viterbo he had a prisoner immersed in a spring of boiling water called Pelacano […] Braccio believed neither in Heaven nor in Hell, was an enemy of the Church and of religion and absolutely unworthy of receiving religious obsequies.» (Enea Silvio Piccolomini, in Niccolò Ciminello, The War of the Eagle. Anonymous Singing of the 15th Century, edited by Carlo De Matteis, Edizioni Textus, anastatic reprint of 1996)

«Braccio was a handsome man, although handicapped on the left side; his speech was sweet and caressing; however, he had a cruel temperament to the point of laughing while ordering people to be tortured and torn to pieces with atrocious torments, and to delight in throwing poor people from high towers. In Spoleto he gave the order to throw a messenger who had brought him a hostile letter from a bridge. In Assisi he threw three men from a tower that rises in the main square. In the convent of the Friars Minor he gave the order to punish eighteen monks who had hostile feelings towards him, by crushing and crushing their testicles on an anvil. In Viterbo he had a prisoner immersed in a spring of boiling water called Pelacano […] Braccio believed neither in Heaven nor in Hell, was an enemy of the Church and of religion and absolutely unworthy of receiving religious obsequies.» (Enea Silvio Piccolomini, in Niccolò Ciminello, The War of the Eagle. Anonymous Singing of the 15th Century, edited by Carlo De Matteis, Edizioni Textus, anastatic reprint of 1996)