Corporations, which in the Middle Ages were called Arts or Crafts, represent the most common form of work organization in Italian cities, starting from the first municipal age. They essentially represent the association of all those who practice the same trade or the same profession in a given city: masters, apprentices, wage earners.

In northern and central Italy, associations of merchants and manufacturers (the future major Arts) were formed as early as the 12th century, which aimed at the early division of municipal power. The statutes that governed them, which were very rare before the 13th century, were a set of ratifications of professional customs, police measures and confirmations of rights, and were modeled on municipal statutes. Usually, the Statute or Brief of the corporation was limited by the municipal one, and it is no coincidence that it was often the municipal authority itself that authorized its drafting and ratified it, in order to avoid conflicts of competence and interests. The Statute or the Brief were composed of chapters or rubrics, of which:

- some were dedicated to the election, oath, functions, rights and duties of the representatives and administrators of the Corporations (Captains, Councilors, Chamberlains, Notaries, Family Members)

- others concerned the rules of mutual aid between members (financial aid among the poor of the Art, assistance to the sick, funerals of members)

- others regulated the life of the association with a description of the rights and duties of all members and rules of professional ethics

- others regulated the relationships between masters, apprentices, workers

- others regulated the registration to the Brief, the oath of the new member, the registration fee, the membership fees

- others established the way of honoring the holidays

- others provided for rather severe pecuniary penalties for those who did not respect the individual Chapters.

The new regime, based on the laboratory or family workshop, actually strengthened the position of the masters who closely monitored the apprenticeship and regulated access to the profession. The lowest rank within the corporation was that of the garzone, who carried out unskilled work; to become a master it was necessary to spend a period of training with one of these as an apprentice. This period ended with a sort of final exam, consisting of the preparation of a masterpiece, with the aim of demonstrating the technical skills acquired.

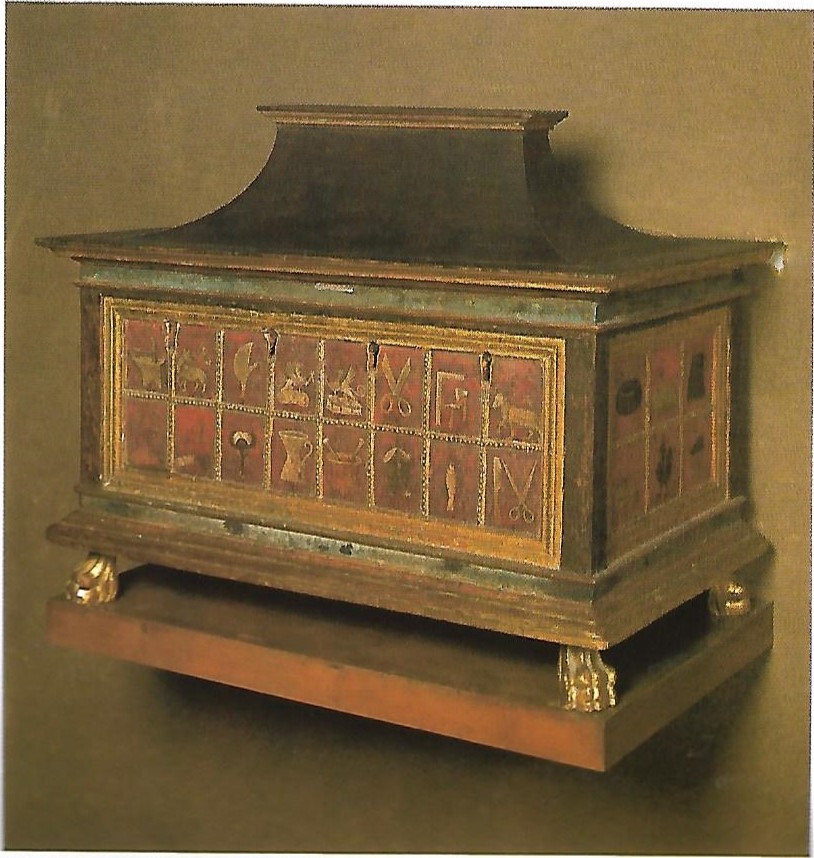

In Perugia the list of the Arts appears in chapter 38 of the first book of the Statutes of the Municipality and People of Perugia of 1342 in the number of 43; while in the number of 44 they are remembered by the emblems painted on a chest from the 15th century existing in the National Gallery of Umbria. A financial document from 1368 allows for the establishment of a hierarchy between the corporations mainly based on their economic potential. At the top are the arts of Merchant and Money Change, followed by notaries, painters, shoemakers, tailors, fishmongers, blacksmiths, stone and wood masters, wool and wool cloth workers, procurers, butchers, tavern keepers, potters, cobblers, sword makers, stationers, cowherds, basket makers and basket makers, bakers, barbers, dyers, goldsmiths, silk and cotton workers (banbacari), chicken farmers, greengrocers.

In Gubbio the first reliable news of the existence of corporations of the arts dates back to the second half of the 13th century, but it is only from the statute of 1338 that we deduce their number; in addition to judges and notaries, there were 15 arts (some of which grouped together different trades): they were the arts of the guarnelli weavers, merchants and money changers, wool workers, dyers and stationers, shoemakers, bricklayers and stonecutters, carpenters, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, swordsmiths and armorers, tanners and tailors, butchers, haberdashers, millers, potters, doctors and apothecaries, barbers.

In Assisi the most important corporation and already solidly organized at the end of the 12th century was that of the Merchants. In a municipal act of 1233 it is documented with the companies of tax collectors, butchers, and shoemakers. In the manuscript statute of 1468 we find a list of 19 arts and it includes wool workers, shoemakers, weavers of gauze and cotton, and dyers.

In Foligno the historical development of the Arts began at least at the beginning of 1200. In 1401 there were twenty-two: “Ludices et notarii, mercatores, cannaparii, spetiarii, mercerii, fabri, cozolarii, lanarii, carpentarii, funarii, butchers, pizzicharoli, fornarii, tabernarii, molendinarii olei, molendinarii grani, muratores et fornachiarii, vasarii”. Ninety years later five more come to light: cerdones, magistri petre et lignaminis, aurifices, salinarii, venatores.

In Trevi in 1524 there were a considerable number of professions: notaries, judges, doctors, shoemakers, merchants, plowmen, carpenters, bakers, barbers, squires, blacksmiths, coppersmiths, gunsmiths, watchmakers, cloth weavers, millers, innkeepers, butchers, greengrocers, rope workers, decorators, wool workers, tailors, sawyers, glassmakers.

In Todi, in 1317, the arts numbered twenty-three: merchants, shoemakers, haberdashers, goldsmiths, cobblers, tanners, wool workers, cotton, linen and hemp weavers, blacksmiths, kiln workers, carpenters, innkeepers and innkeepers, potters, pork butchers, butchers, barbers, greengrocers, bricklayers, potters, millers, judges and notaries. In subsequent reforms of 1332 and 1439 the same arts appear.

In Orvieto the list of arts is found in a document from 1295 and includes 24 organized professions and trades: judges and notaries, merchants, wool workers, shoemakers, haberdashers, butchers, blacksmiths, furriers, tailors, bricklayers, procurers, tavern keepers, pork butchers, carpenters, millers, wage earners, rope makers, innkeepers, fruit and vegetable sellers, barbers, lime workers, potters, grinders, carters. In 1316 there are also the arts of goldsmiths, plowmen, and perfumers.

In Spoleto, in a register of reformations from 1362 and one from 1517 they number fifteen and among them goldsmiths, notaries, and judges. In a register of reformations from 1664 there are no more than five. A few years later, in 1673, there were a considerable number of them: potters, bakers, innkeepers, butchers, pork butchers, shoemakers, tailors, bricklayers, carpenters, blacksmiths, hatters, haberdashers, goldsmiths, apothecaries, merchants and bankers, silk workers, wool workers.

In Nocera Umbra, the Statute, which has reached us in the printed version of 1567, encourages and regulates the arts: Wool, Paper, Guarnelli (garments made of hemp and linen), Cervellieri (headgear made of metal and leather), Apothecaries, Bakers, Taverniers, Pork butchers, Butchers.

In Bevagna the Statute, which has come down to us in the sixteenth-century edition (the statuary chronology seems to move between 1334, 1417-31, and indeed 1500) regulates the arts of hemp and wool weavers, innkeepers and tavern keepers, butchers, master carpenters and stonemasons, bakers, pork butchers, millers, blacksmiths, potters, brick makers, wax workers, and millers.

The Art of Silk and its Reconstruction in the Gaite Market and in the Gaita Santa Maria

Nella rievocazione storica del Mercato delle Gaite una delle quattro gare in cui le quattro gaite si sfidano è quella dei Mestieri che prevede la ricostruzione di mestieri medievali il cui esercizio risulti storicamente documentato per l’arco temporale di riferimento (1250-1350). Secondo il regolamento il termine mestieri va inteso nella sua accezione di Ars ossia quella di una specifica e ben individuata attività svolta da esseri umani e finalizzata alla produzione di un bene o all’erogazione di un servizio. Nella gara devono essere riprodotte, sulla base di fonti storiche dell’epoca di riferimento, le varie fasi dell’attività rappresentata. A tale scopo devono essere utilizzati materiali, strumenti e tecniche proprie dell’epoca, riprodotti nelle stesse caratteristiche e forme.

La scelta dell’arte della seta deriva sia dalla consapevolezza dell’importanza che tale attività assumeva nell’Italia del basso Medioevo, sia perché, fino a qualche decina di anni fa, grazie alla diffusione del gelso nel territorio, le donne di Bevagna si dedicavano in gran numero all’allevamento del baco e alla raccolta e vendita dei bozzoli. La Gaita ha deciso di riprodurre tutte le fasi di questo complesso ciclo di lavorazione, dall’allevamento del baco da seta – pratica ormai rarissima da osservare nell’Italia di oggi – alla tessitura del prezioso filo, passando attraverso le fasi della trattura, della torcitura, della tintura e dell’orditura. L’allevamento inizia facendo schiudere le uova conservate dall’anno precedente. Non appena esce dall’uovo, il baco da seta è una minuscola larva che inizia a mangiare le tenerissime foglie di gelso. Questo è un periodo di rapida crescita a cui, dopo una giornata di sonno ininterrotto, segue la prima mutazione. Il filugello cambia quattro volte l’involucro chitinoso che gli avvolge la pelle prima che possa raggiungere la maturità e poter tessere il bozzolo. Dalla schiusa delle uova al bozzolo trascorrono 30 giorni durante il quale il baco viene ad essere alimentato ogni tre ore. 4 mute per cinque età, un consumo di foglia che varia da 3 kg per la prima età a 770 kg per la quinta, un aumento di lunghezza da mm 3 alla nascita a 45 mm alla quinta età fino a 90 mm a maturità completa (aumenta di 30 volte), un aumento di peso da gr 0,00056 fino ad 1 gr alla quinta età e 4 gr a maturità completa (aumenta di 8000 volte). Verso il settimo giorno della quinta età il baco cessa di nutrirsi, svuota completamente il suo intestino e tramite le sue due lunghissime ghiandole serigene tubulari inizia la costruzione del bozzolo che dura da tre a quattro giorni; al termine il baco con una nuova muta si trasforma in crisalide. Miliardi di crisalidi in procinto di uscire dal loro bozzolo vengono uccise con il calore, al sole, per impedire alle aspiranti farfalle di secernere il liquido alcalino che sciogliendo le sostanze gommose del bozzolo crea il foro d’uscita. Dopo la strage, il miracolo. I delicati involucri sierosi riescono a ridonare tutto il filo che li compone. Il primo procedimento nella preparazione di un filo di seta è la trattura: i bozzoli vengono immersi in acqua bollente per rendere il materiale legante viscoso e vengono rimossi con bastoni, alle estremità dei quali aderiscono i filamenti di seta. Il peso del bozzolo varia da 1,8 a 2,5 gr, la lunghezza della bava serica dai 1500 ai 2500 m; da 100 gr di bozzoli si ricavano 20/25 g di seta; per ottenere 1 Kg di filo di seta occorrono più di 10 kg di bozzoli. I filamenti sono avvolti su un aspo: essendo i filamenti di seta troppo delicati per essere avvolti uno alla volta, se ne avvolgono insieme un certo numero, da tre ad otto. La successiva operazione consiste nell’incannatura, ossia nel passaggio dalle matasse di seta avvolte intorno all’arcolaio ai fili avvolti in rocchetti di legno. Successivamente i fili di seta vengono ritorti (filatura e torcitura) per impedire che i singoli filamenti si separino. Di notevole valore è la ricostruzione del torcitoio circolare da seta. Il torcitoio da seta è la prima macchina operativa complessa che l’uomo abbia mai ricostruito. Dopo la torsione le matasse di filo di seta vengono collocate in sacchetti e bollite in acqua saponata (cocitura) per eliminare la gomma naturale che può ostacolare la tintura; vengono poi sciacquate in acqua pura e messe ad asciugare. Quelle di color perlaceo vengono poi sbiancate con i vapori di zolfo (inzolfatura); così il filo bianco è pronto per la tintura. I principali coloranti utilizzati per la tintura della seta erano la robbia e il verzino per le varie gradazioni di rosso, il guado e l’indaco per gli azzurri, la guaderella e il sommaco per i gialli, le noci di galla per il nero; il verde si otteneva combinando guado e guaderella, mentre le celebrate e preziose tinture in scarlatto avevano bisogno del chermes, il più costoso di tutti i coloranti, derivato dai corpi essiccati di una specie di pidocchio che viveva sui lecci e su altre varietà di quercia mediterranea. Uscita dalle tintorie, la seta torna nelle mani delle incannatrici che avvolgono i fili di trama sui rocchetti; questi vengono spediti nelle case di altri lavoratori serici per l’orditura. Predisposto l’ordito tutto è pronto per la trasformazione decisiva, la tessitura. L’elemento di raccordo tra i diversi poli operativi è costituito dalla bottega di seta, dove i setaioli, coadiuvati da uno staff di fattori svolgono le funzioni organizzative, amministrative e commerciali indispensabili per il funzionamento dell’azienda disseminata.

Nella ricostruzione degli strumenti di lavoro utilizzati, dalla fornace per scaldare l’acqua e immergervi i bozzoli, al grande aspo per raccogliere il filo in matasse, uno sforzo particolare è stato dedicato alla ricostruzione del congegno utilizzato per la torcitura del filo di seta, il torcitoio a trazione umana, considerata dagli specialisti come la prima macchina operativa complessa che l’uomo abbia realizzato e come tale alle origini della civiltà industriale, facendone l’unico esemplare esistente e funzionante al mondo.

Durante la manifestazione, il torcitoio è certamente, fra gli strumenti d’epoca presenti, il più prestigioso per il suo valore storico e culturale e inoltre, nell’ambito di una riproduzione il più fedele possibile di mestieri medievali, è sicuramente la macchina riprodotta nel modo più corretto per quanto riguarda le fonti di energia, immune dalla contaminazione con le tecnologie moderne (corrente elettrica, metano) utilizza solo la forza delle braccia.

L’Arte della seta in Umbria

A Perugia la lavorazione della seta inizia nella prima metà del Quattrocento. Nel 1529 l’arte dei bambacari chiese e ottenne di unirsi con i setaioli. I bambacari e i setaioli costituirono il Collegio della seta e della bambagia (mantenendo tuttavia separati i propri statuti) nel 1529. In seguito, la necessità di raggiungere un più razionale impiego delle risorse economiche convinse dell’opportunità di riunire le due arti. La nuova istituzione assunta la denominazione di Arte della Seta e della Bambagia, redasse gli statuti nel 1531. Nel 1543 vennero elaborati gli statuti definitivi dell’arte. Redatte in volgare, le disposizioni sono comprese in sessantadue capitoli, di cui quarantotto riguardano l’arte della seta e quattordici quella della bambagia.

Capitolo 1. Che li merchatante de l’arte de la seta siano tenute de bollare rocche e channone con loro sengno.

Capitolo 5. Che li filatoiaie siano obligate filare et diligentemente a usu de bono e liale maestro.

Capitolo 7. Che niuno filatoio o torcetore possa filare né torcere seta a frostiere né a chi non ha bothiga in piaçca.

A Foligno, già negli 1471-1472, due mercanti imprenditori forestieri manifestano il desiderio di introdurre l’Arte della Seta. Ma solo nel 1540 vengono elaborate tre bozze degli statuti dell’arte, due delle quali abbastanza simili e composte da 15 capitoli e 17 capitoli.

Capitolo 1. In primis che alcun foristero che non sia habitante in Foigno per anni 30 et habbia casa et possessione non possa lavorare, ne fare lavorare.

Capitolo 2. Item che tucti quilli che vogliono lavorare o far lavorare siano matriculati ad larte de la seta.

Capitolo 8. Item che nessun filaturaro, ne tintore, possano torcere, ne torcere, ne filare, ne tignere in alcun modo, alcuna generatione de seta ad nessun foristero, ne ad alcun altro che non sia matriculato et scritto ad larte sotto pena.